Article authored by:

Brad Bass, PhD

A Simcoe Chapter member, Dr. Brad Bass is a 30-year veteran at Environment and Climate Change Canada as well as a Status Professor at the University of Toronto. Dr. Bass led the development of COBWEB (Complexity and Organized Behaviour Within Environmental Bounds) in 1999. COBWEB, is now used by students to simulate the performance of vertical flow constructed wetlands, urban segregation, and retail locations. In 2012, Green Roofs for Healthy Cities awarded Dr. Bass the Lifetime Achievement Award for Green Infrastructure Research. Dr. Bass’ most recent work on the cost of algal blooms was published in July 2019.

This article presents an argument on the need for reviving the urban street vitality, integrating the revival with green infrastructure and maintaining the viability of low-income neighbourhoods.

This piece was originally written as part of a larger policy discussion around a Canadian green stimulus in response to the COVID-19 economic disruption. It has been revised to emphasize the need for social interaction and to include some original modelling work from Brad Bass' research program at the University of Toronto.

Since writing this article, the urban role of main streets and vibrant streets has received attention in a number of other publications and news talk shows. In addition, the Canadian Urban Institute has launched their Bring Back Main Street initiative, a nationally-coordinated research and action campaign to ensure the survival of Canadian main streets in the post COVID-19 economy.

Restarting The Street Economy: an essential part of the economy

Much of the economy takes place in cities, and Canada is no different from other countries in this economic geography. Economic activity, i.e. the Canadian economy, is concentrated in Canada’s cities (Brown and Rispoli, 2014). Three Canadian cities – Toronto, Montreal and Vancouver – have been the fastest growing populations in Canada and are the Canada’s locus for finance, commercial activity, education and research, manufacturing, tourism, innovation and creative activity (Schwartz, 2011). What drives economic activity in cities? Creativity, which is driven by a highly educated population and a breadth of differences between members these populations (Schwartz, 2011).

Highgrowth cities have a wide range of cultural activities and a social environment characterized by the tolerance of difference and nonconformity and by low barriers to entry into both the social networks and the labour market.

To derive the benefits of this creativity requires an environment that generates encounters. Cities with their high densities, provide this environment. In a sense, this is the creative version of agglomeration or clustering (Porter, 1998; Krugman, 1995). Agglomeration or clustering creates an economic benefit for industry, when the firms in that industry and related industries reduce the cost of interaction. This leads to the creation of partnerships, sharing of knowledge and increasing the breadth of talented people. However, the model can be applied to urban retail (Krugman, 1995; Ma, 2020, Figure 1). Another benefit of higher densities is the green benefit. Higher density cities driving down private transportation and the per person energy intensity (Owen, 2010). However, the reduction of permeable surfaces that occurs with higher densities creates problems for managing stormwater runoff. This issue is also addressed in this proposal, because green infrastructure can be part of street vitality; reopening the urban economy is not just an economic stimulus, but it is also a green stimulus.

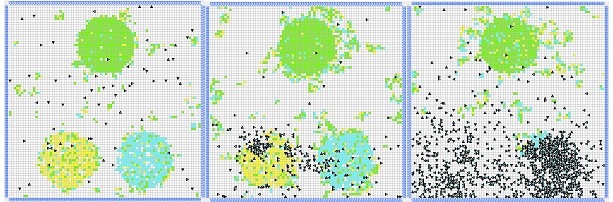

Figure 1: Illustration of the Clustering Effect with COBWEB (Ma, 2020).

Note how the cluster, represented by the closeness of the blue and yellow circles draws customers, while the traffic at the green circle is relatively light.

The benefit of creative clustering requires a critical mass in the same urban area. This provides opportunity to work with and learn from people in similar professions as well as people who are in dissimilar fields –– in fact Schwartz (2011) uses the term and stresses the importance dissimilar creativity –– provides the opportunity to learn from other people in a range of fields, generates novel ideas and contributes to a strong a tolerance of difference. Encounters with other creative people will drive new ideas. The importance of dissimilarity is echoed by Sunstein (2019) in his discussion on how a lack of disagreement breeds conformity, but not always the best results. A recent briefing in The Economist (2020) noted the importance of public places, cafes, pubs and similar institutions as fora for exchanging ideas and the importance of face-to-face meetings for innovation.

The previously mentioned briefing in The Economist (2020) also noted that we may have a world in which our places of work are open, but the pubs are closed, either because they have shut down, or psychologically, we are closed to social gatherings. Even if pubs, restaurants, theatres and public squares are open, they are not open if we avoid them out of concerns for personal safety. A less social world will affect the very institutions and spatial arrangements that are often associated with the vibrancy of cities. West (2017) maintains that a doubling of urban populations increases the aggregate wealth by 15%, but this doesn’t happen without those social aspects of urban life.

A city must have a vitality that draws creative to live and work in the same areas. Where is that vitality found? It has to start on the street, an argument first made by Jane Jacobs (Jacobs, 1961). What keeps a streetscape vital is what makes it interesting to walk down, why some streets just appear to draw people to them –– a blend of clustering, dissimilar retail and other small establishments. Restarting the urban economy must be a priority in reopening the economy. To restart the urban economy, it is necessary to reopen the streets.

Reopening the street may require thinking about reviving the street. Vital streetscapes were already facing competition from online shopping. In the US, 75,000 stores will close by 2026 due to online shopping (Whiteman, 2020). Retail was already beginning a restructuring process, which some industry experts were calling the “retail apocalypse” (Helm, Kim, & Van Riper, 2018). This trend is only being exacerbated by the pandemic. Although retail experts are not yet decrying the end of the bricks and mortar establishment, its role in retailing will have to change. Whereas the “website” used to function as a means to drive people to the store, now the store must be a way to drive people to the website.

While the trend towards higher densities in urban planning encourage a vibrant street life, the vibrant street life and the higher densities have a positive impact on reducing energy consumption per person. The same cannot be said for the impacts on water quality and flooding, due the imbalance that is typically found between impermeable and permeable surfaces. There are many green infrastructure options for addressing this issue, but the focus here is on options that also maintain or increase the vitality of streetscapes because they draw people to the street.

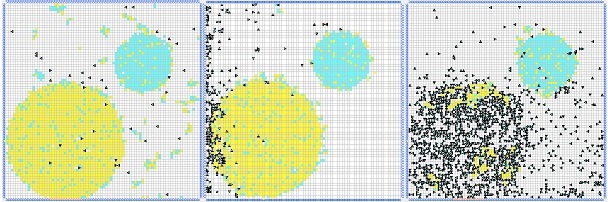

Portas (2020) noted that with the acceleration of online retail, only exceptional brands and places will survive on the street. Increasing the visibility of a store is one way to increase foot traffic in the area (Ma, 2020, Figure 2). Green walls are now being used by retailers on building exteriors to attract customers (Mannion, 2019). Although this may seem like a recent development, the green wall industry has recognized this benefit, formally, since 2009 (Green Roofs for Healthy Cities, 2009). Green walls also provide a means to connect with environmentalists, gardeners and other plant lovers.

Green walls have an impact on stormwater runoff, but it is not a major benefit compared to green roofs and street level infrastructure (large planters, bioswales and trees). Fortunately, street level green infrastructure, which does have a large impact on stormwater runoff, is a net benefit to commercial property (Clements and St. Juliana, 2013). For the purposes of the reviving the street, trees can increase retail sales by increasing the attractiveness of a shopping area, and street level plants have also been recommended to increase retail traffic (Ambius, 2015; GreenBlue Urban, 2018). The Liquor Control Board of Ontario has installed outdoor, full-season planters at one outlet in Toronto as an aesthetic feature (Genetron Systems, 2015).

Figure 2: Note how the more visible location, represented by size, draws far more customers than the blue location (Ma, 2020).

What are steps that government must take to reopen the street so it is still the driver of urban vitality?

- Diversity comes from independent retail, primarily, rarely from chains. If independent retail is forced out of business, those locations will be prime locations for the large chains. Although a streetscape of different chains may still be of interest, it is not worth a special trip when those same streetscapes exist everywhere else, and certainly will not be a draw to tourists.

- Ensure that diverse streetscapes maintain their diversity by providing funding now so that these small establishments can reopen in an environment that will still operate under the practice of social distancing

- Begin discussions now with local community associations and BIAs to tailor policies to local areas; don’t assume a one size fits all

- Encourage co-location of services or establishments that require site visits to collocated on these streetscapes (i.e. healthcare, legal services)

- If the economy is reopened in phases, prioritize these areas along with transit to these areas

- Provide the consulting services of retail and marketing gurus to these establishments

- Governments should engage or re-engage with municipalities on green infrastructure if they have expertise in this area

Another countervailing trend in cities is increasing segregation by income. Although this trend has been noted in Toronto in the last few years, it was studied in in several US cities where it was found that increasing innovation, measured by patents, contributed to a 20% increase in urban segregation by income from 1990 to 2010. This income segregation was accompanied by educational and occupational segregation especially in sectors such as IT and electronics (Berkes and Gaetani, 2019). Part of what drives innovation can threaten what makes creativity work by driving a high degree of segregation that decreases dissimilarity and increases conformity.

The segregation pushes lower income earners out to the periphery (Bradford, 2018; Feise and Pettem, 2018). What this does is reinforce an atmosphere of similarity, not dissimilarity on the street, which leads to a spatial conformity that can reinforce segregation. This echoes a comment on urban policy in Bradford (2018) on how urban social and physical infrastructure can “entrench exclusion”, and exclusion that can be both spatial and social. Can the Federal Government play a role to maintain neighbourhoods that are integrated or are low-income areas near the vibrant downtown core? The Federal Role might be to target existing payments to these communities to support residents through rent subsidies, wage subsidies and deferred tax payments specifically directed to these communities. More creatively, the Federal Government could recognize the social, the green and the physical infrastructure in these streetscapes as essential economic infrastructure that requires investment.

Most of Canada’s economy is urban, and most of the global economy is increasingly urban (UN, 2009). This proposal has made the argument that a vibrant street life is important for urban vitality and in turn, the urban economy. Reviving the urban street is also a green policy because it reduces energy consumption per person and can incorporate green walls, trees, planters and bioswales. Reopening and reviving the urban streetscape will not only maintain urban vibrancy and the health of the urban economies, but it can be done in a way that addresses multiple environmental issues, some which will be exacerbated because of climate change, as well as social disparities. The street is not only the focal point for thinking about urban vibrancy, but it can be the focal point in rethinking our post-pandemic, decarbonized and vegetated, i.e. greener, economy.

Brad Bass with University of Toronto students |

A lovely flower garden accents the street side outdoor dining in Victoria, BC. |

A University of Toronto student, Ara Negapatan, |

An informative sign accompanies the Blake Street Tree Pit. |

Brad Bass sitting with a streetscape sculpture (Ithaca NY). |

An eclectic alley way in Kingston, |

All pictures are courtesy of Brad Brass.

References

Ambius (2015) The Importance of Plants in Retail Environments. https://www.ambius.com/blog/the-importance-of-plants-in-retail-environme...

Berkes, E., & Gaetani, R. (2019). Income Segregation and Rise of the Knowledge Economy, Rotman School of Management Working Paper No. 3423136. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3423136 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3423136

Bradford, N. (2007) Whither the Federal Urban Agenda: A New Deal in Transition, Research Report, No. F65 (Ottawa: Canadian Policy Research Networks, 2007).

Bradford, N. (2018) A National Urban Policy for Canada? The Implicit Federal Agenda. IRPP Insight 24. Montreal: Institute for Research on Public Policy.

Brown, M. and Rispoli, L. (2014) Metropolitan Gross Domestic Product: Experimental Estimates, 2001 to 2009, Economic Insights. 11-626-x no. 042, Statistics Canada, Ottawa

Canadian Urban Institute (2020) Bring Back Main Street. https://bringbackmainstreet.ca

Clements, J. and St. Juliana, A. (2013) The Green Edge: How Commercial Property Investment in Green Infrastructure Creates Value. The National Resources Defense Council, December 2013 R:13-11-C

Economist (2020) Not quite all there. Briefing section. The Economist April 30, 2020 edition.

Feise, A, and Pettem, J. (2018) Segregation and the Knowledge Economy: Modelling Trends using COBWEB Software. Unpublished Report completed in Brad Bass’ Lab, Research Opportunity Program, Faculty of Arts and Science, University of Toronto.

Genetron Systems, Inc (2015) Personal Communication

Green Roofs for Healthy Cities (2009) Green Walls 101: Systems Overview and Design, 2nd Edition. An introductory half-day course for professionals. Green Roofs for Healthy Cities, Toronto ON.

GreenBlue Urban (2018) Encouraging Increase in Retail Sales with Urban Trees. https://www.greenblue.com/na/encouraging-increase-in-retail-sales-with-urban-trees/

Helm, S., Kim, S. H., & Van Riper, S. (2018). Navigating the ‘retail apocalypse’: A framework of consumer evaluations of the new retail landscape. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, doi:10.1016/j.jretconser.2018.09.015

Jacobs, J. (1961) The Death and Life of Great American Cities. New York, NY: Random House. 458 p. (1989 ed.)

Krugman, P (1995) The Self-Organizing Economy. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell, 132 p.

Ma, M.Y. (2020) Using COBWEB to Measure the Effects of Key Factors Influencing the Success of Retail Businesses. Unpublished Report completed in Brad Bass’ Lab, Research Opportunity Program, Faculty of Arts and Science, University of Toronto.

Mannion, A-M. (2019) Green Walls, a Growing Retail Feature. Shop Retail Enviornments. Sept-Oct 2019. https://www.retailenvironments-digital.org/retailenvironments/september_october_2019/MobilePagedArticle.action?articleId=1523491#articleId1523491

Owen, D. (2010) Green Metropolis: Why Living Smaller, Living Closer, and Driving Less Are the Keys to Sustainability, New York, NY: Riverhead Books, Reprint edition, 368 p.

Portas. M. (2020) The cull of retail businesses spells the end for mediocre malls. Financial Times

Porter, M. (1998) Clusters and the New Economics of Competition. Harvard Business Review. November-December 1998.

Schwartz, H. (2011) The Economic Effects of Large Cities on the Canadian Economy. Policy Options, policyoptions.irpp.org/magazines/provincial-deficits-and-debt/the-economic-effects-of-large-cities-on-the-canadian-economy/

Sunstein C. R. (2019) Conformity. New York, NY: New York University. 183 p.

UN (2009) World Population Prospects: The 2008 Revision and World Urbanization Prospects: The 2009 Revision. Population Division of the Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations Secretariat, World Population Prospects: The 2008 Revision and World Urbanization Prospects: The 2009 Revision

UN Habitat-OECD (2016). State of National Urban Policy. https://www.oecd.org/gov/habitat-3-and-a-new-urban-agenda.htm

West, G. (2017) Scale: the universal laws of growth, innovation, sustainability and the pace of life in organisms, cities, economies and companies. New York, NY: Penguin Press. 481 p.

Whiteman, D. (2020). These Chains Have Announced a Ton of Store Closings in 2019. MoneyWise, https://moneywise.com/a/retailers-closing-stores-in-2019

Members please log in to leave comments.